The UK’s economic reputation was forged by the industrial revolution two centuries distant and, given the uncertainty of Brexit, it is easy to lapse into laments about bygone glories. But questing minds and the relentless pursuit of solutions are propelling a fresh revolution that, although not wreathed in furnace steam and belching fumes, is delivering global success.

The life sciences sector, covering pharmaceutical and clinical innovation and pioneering technology, is providing sinew to the economy and hope for patients who want to enjoy their now longer life expectancy free from debilitating conditions.

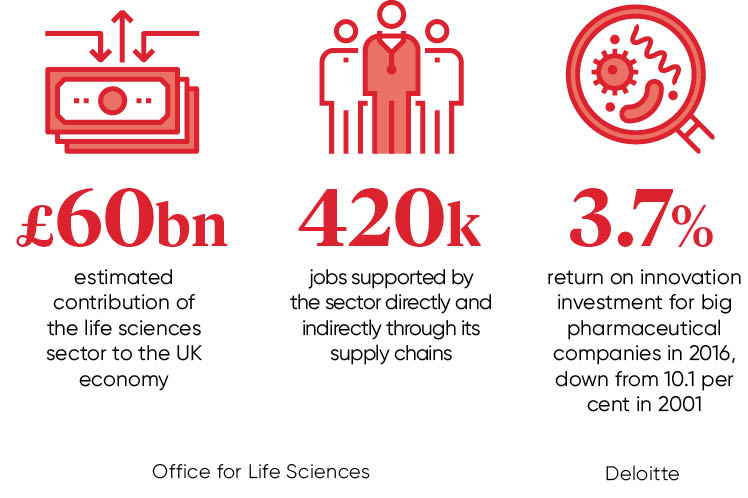

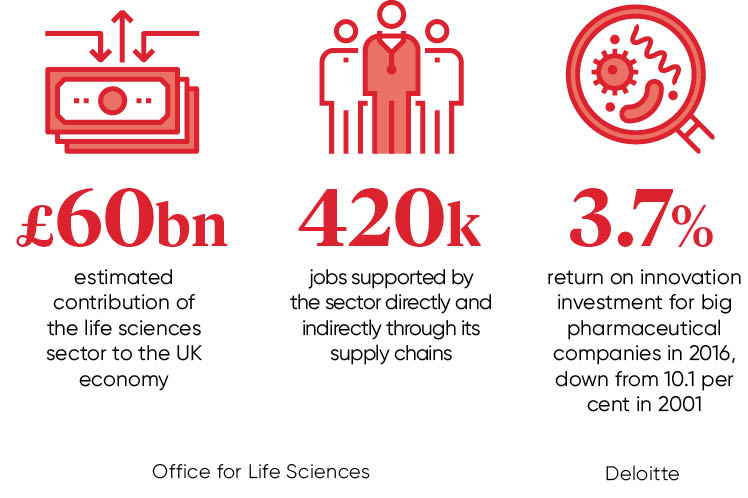

The sector pumps £60 billion into the UK economy and supports around 420,000 jobs directly and in supply chains, according to government figures. It is unashamedly described as “one of the jewels in the crown” of the UK economy.

“We have four of the top six universities for clinical, pre-clinical and medical research, and three of the top ten medical schools in the world which is very impressive,” says Karen Taylor, research director of the Centre for Health Solutions with analysts Deloitte. “The combination of academia, life sciences and healthcare creates an energy, and is attractive to investment.

“The sector is showing resilience and investment gives the government confidence it can remain an important element of the economy.”

The investment figures have been charging upwards – the quoted value of the sector rose from £40 billion in 2015 to nearly £400 billion this year, according to figures from the London Stock Exchange in January – and Brexit has, so far, not put the brakes on.

Government focus

Ms Taylor believes the seeds for current growth were sewn in David Cameron’s Conservative administration and have continued to flourish with tax incentives, development strategies and catalyst funds.

“2017 is predicted as being another strong year,” she says. “The attraction of our universities will not diminish. A combination of an innovative and vibrant life sciences sector brings wealth to the country not just in terms of employment and investment, but also in improving the health of the nation.”

The government’s appetite for life sciences seems unadulterated by Brexit as chancellor Philip Hammond’s Autumn Statement, delivered five months after the landmark vote, featured a £2-billion provision for research and innovation which favoured life sciences.

The sector also received star billing in the Great Repeal Bill: White Paper, published last month, which outlines 12 negotiating objectives for exiting the European Union, including making the UK “one of the best places in the world for science and innovation”. Significantly, this goal comes with a “desire to continue to collaborate with Europe on scientific initiatives”.

The financial imperative of a strong life sciences strand to the economy is matched by the need to address the nation’s future health needs, characterised by a creaking National Health Service in search of £20 billion in service savings by 2020 and the population growth of over-65s who are more vulnerable to co-morbidities.

The sector is showing resilience and investment gives the government confidence it can remain an important element of the economy

Population modelling is cloaked in dire warnings for the NHS as, by 2039, the over-65s are expected to represent 23 per cent of the population or 17.5 million people, according to the Office for National Statistics. About one in twelve of the population will be aged 80 or over by then.

More treatment needs for longer is not exactly bright mood music for an institution struggling to cope with its role of seeing one million patients every 36 hours.

But Sarah Haywood, chief executive of the influential MedCity UK, the political-private-academic collaboration that promotes life sciences in London and the South East, says: “There are questions and challenges, but there is great positivity about the future. We also have a very entrepreneurial culture with lots of companies setting up with passion and ambition in healthcare.”

The impact of Brexit

However, she cautions that access to the global talent, which is a prime element of the nation’s academic and innovative attraction, needs to be carefully managed as the UK untangles itself from its EU connections.

Brexit is not the sole disruptive influence in life sciences as the big beasts of the pharmaceutical industry have seen return on innovation investment steadily drop from 10.1 per cent in 2001 to 3.7 per cent in 2016, according to research by Deloitte. Many are restructuring their business models as they grapple with tighter regulations and financial squeezes as well as shrinking profits, claim analysts PwC.

The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry has also warned that the biggest drug companies could abandon the UK if treatments continued to be rationed in a cash-strapped NHS. Its president Lisa Anson, who is also head of Astra Zeneca UK, called on the government to be ambitious to ensure the NHS had world-class status.

Huge advances in novel drugs and the promise of immunotherapy and gene therapy are causes for celebration, but these triumphs are stalked by the towering burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and the financial constraints of healthcare systems.

The World Health Organization reported last month that NCDs, such as cardiovascular disease, cancers, respiratory diseases and diabetes, kill 32 million people worldwide annually.

The great hope is that devices, monitors and systems driven by artificial intelligence can energise diagnostic and preventative measures so the ruinous surge of NCDs can be arrested.

Public policy research centre the Rand Corporation recently published a paper on financial incentives for individuals and communities to promote better health, underscoring the view that exciting developments in healthcare will be handcuffed to some fundamental changes in how the public behaves.

The healthcare landscape is dynamic, and the big challenge is how society and government embrace innovation and remodel the future of health.