This month Apple claimed that its much-feted, but reportedly under-selling, Apple Watch had saved lives. In one case a 62-year-old builder felt terrible after lunch. His watch had revealed an abnormally high pulse and he called an ambulance. Doctors were said to have told him that he might have died if he had gone straight home.

This is a good news story, but medical specialists fear that it may create a misleading impression about the accuracy of personal pulse checkers in hand-held monitors and smartphones.

Apple has not yet marketed its watch as a medical device as this would contravene US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rules. The Apple Watch is categorised as a “wellness tool”, leaving it outside FDA jurisdiction. But all this may change as Apple is collaborating with the world-renowned University of Stanford in a study to see if its watch can detect cardiac arrhythmias or irregular heartbeats such as atrial fibrillation (AF).

If it is successful in rigorous clinical trialling, it could be reclassified as an FDA-approved medical device. This could boost sales at a critical time for Apple, but cost is a major constraint; price tags for the Apple Watch Series 3 launched in the UK last week range from £329 for £1,349.

There are cheaper alternatives, but are they accurate and safe? The question about when an app ceases to be a wellness tracker or monitor and becomes a medical device is a regulatory quagmire. The medical device industry, like the pharmaceutical, aviation and nuclear industries, is tightly regulated.

In contrast, the booming health app market is more like a free-for-all gold rush. In December 2014, Digital Trends estimated there were some 100,000 health apps, worth about $4 billion, and predicted the market would increase to $26 billion by 2017.

AliveCor’s Kardia Mobile app connects with a clinically approved ECG to detect abnormal heart rhythms and e-mails results directly to the doctor

How many health apps are used as personal pulse checkers? No one knows. How accurate are they? Again, no one really knows. Many apps carry disclaimers that they are not medical devices, but Trudie Lobban, founder and chief executive of the Arrhythmia Alliance and the Atrial Fibrillation Association, fears many apps are being used as such even though they haven’t been tested in clinical trials, which is the only certain way of finding out if a treatment or a diagnostic technique works.

Ms Lobban is concerned because AF, the most common arrhythmia or heart rhythm disorder, significantly increases the risk of disabling or fatal strokes. Inaccurate apps could produce false positives or false negatives, with potentially fatal consequences.

AF can cause a quivering or irregular heartbeat, but some sufferers don’t experience symptoms at all, so their condition is only detectable upon physical examination. More than 1.5 million people in England alone have been diagnosed with AF. Experts estimate that at least a third more remain undiagnosed. With an ageing population, this number is expected to double by 2050.

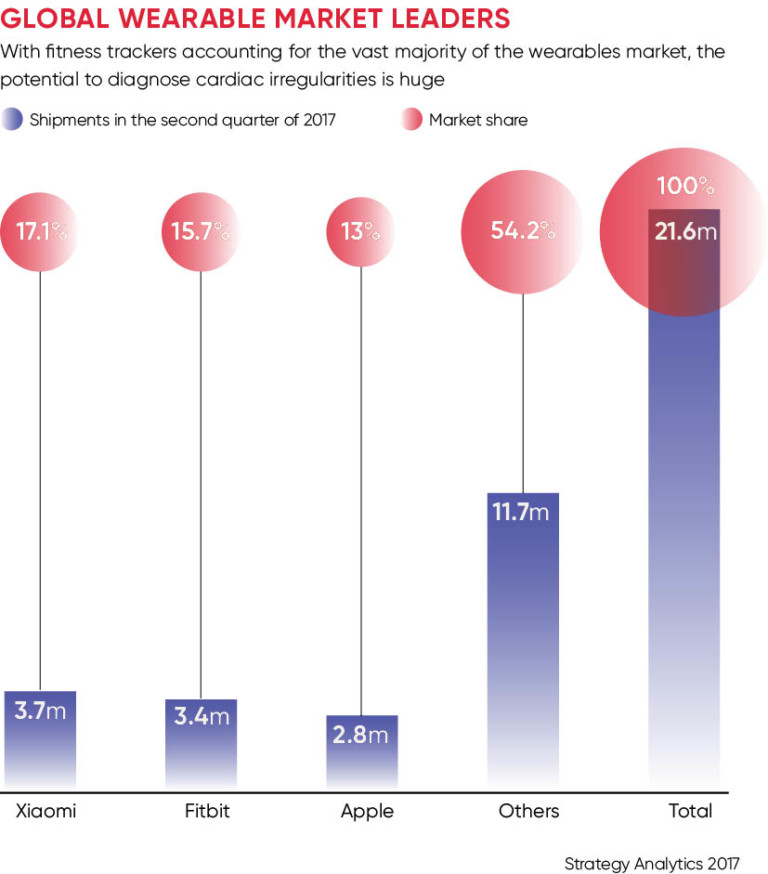

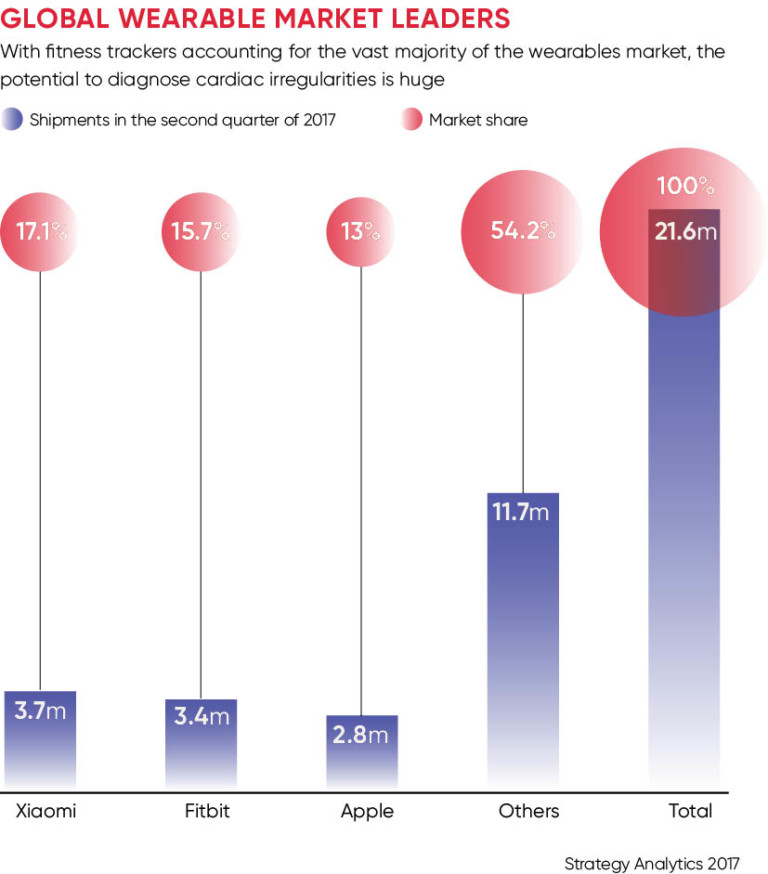

Small wonder then that Apple and other big companies such as Fitbit are playing catch-up in the booming health app market. Last year doctors in New Jersey were able to identify when a 42-year-old patient went into AF by looking at his wristband Fitbit fitness tracker. Fitbit is now researching ways to assist those who suffer from AF by identifying periods when abnormal heartbeats may be occurring.

How can patients in the UK distinguish between fitness or health trackers and medical devices? In law a medical device marketed in Europe must carry a so-called CE mark, which is a declaration from the manufacturer that it meets minimum legal requirements set out in European directives.

The London-based Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) says: “The CE mark should be visible on the app when you are looking at it in the app store or on the further information or ‘landing’ page. If you can’t see these details or are unsure, we suggest you contact the developer to ask and in the meantime that you don’t use it. Please use only medical device apps that are CE marked.”

CE-marked products include AliveCor’s Kardia Mobile for detecting AF. This delivers a medical-quality ECG to a smartphone in about 30 seconds. It had a ringing endorsement in 2015 from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence on the back of successful clinical trials. In one study, researchers at the Chinese University of Hong Kong found that the device was able to identify AF in patients who had not been previously diagnosed.

The CE-marked Preventicus Heartbeats app has also been clinically evaluated in a trial with patients at Barts Heart Centre in London when it was compared to the Beatscanner app. Preventicus enables you to measure your cardiac rhythm with your smartphone camera without any additional equipment. Of 83 patients (59 per cent) with smartphones, 94 per cent were interested in using them to self-screen for AF. Almost all the patients (96 per cent) found the apps easy to use and 63 per cent preferred the Preventicus app, which also had a superior sensitivity rating of 94 per cent compared with 89 per cent.

But the AF Association says the consumer still has to rely on the manufacturer’s promise that a CE-marked product is fit for purpose. Bodies such as the MHRA, Health and Safety Executive, and Trading Standards Services are responsible for enforcing CE-marking legislation, but the AF Association insists that this is not good enough.

In addition, as part of gaining a CE mark, virtually all products marketed by major medical device manufacturers will have been produced to conform to the ISO (International Standards Organization) 13485 quality management system.

There is worrying evidence that health apps should be subjected to more rigorous scrutiny

John Showell, founder of Product Approvals, a device-testing and certification consultancy, says: “ISO 13485 is one of the world’s most stringent quality management systems, but ISO 13485 certification is not mandatory for health apps. This means that a device could obtain a CE mark without having ISO accreditation, but it would first have to be assessed by a so-called ‘notified body’ such as, in the UK, the British Standards Institute (BSI).”

The BSI says: “ISO 13485: 2016 provides the basis for ensuring the consistent design, development, production, installation and delivery of products that are safe for their intended purpose.”

But there is worrying evidence that health apps should be subjected to more rigorous scrutiny. For example, one app purported to measure blood pressure by placing the microphone and LED light of an iPhone on the consumer’s chest. Once among the highest grossing apps in the health section of the iTunes App Store, this was reported to reassure falsely four of every five people with high blood pressure that their blood pressure was not elevated.

In another case, two developers, who claimed their app reduced acne through coloured lights emitted from smartphones, were fined and ultimately removed from the iTunes App Store and the Android Marketplace.

Reform is underway in the form of the new European Medical Device Regulation. The BSI says: “It addresses concerns over the assessment of product safety and performance by placing stricter requirements on clinical evaluation and post-market clinical follow-up.” But the new rules will not apply until May 2020.