First, the good news. The reduction in early deaths from cardiovascular disease or CVD is one of the success stories of modern healthcare. Since 1961, the UK death rate from CVD has fallen by 75 per cent. In the past 15 years alone, early deaths from heart disease have been reduced by 40 per cent. That’s quite an achievement.

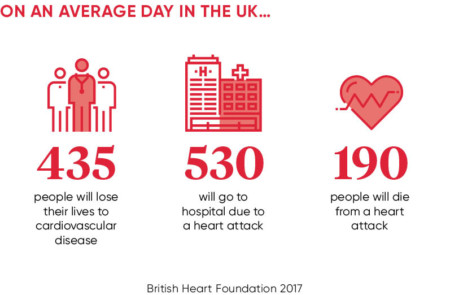

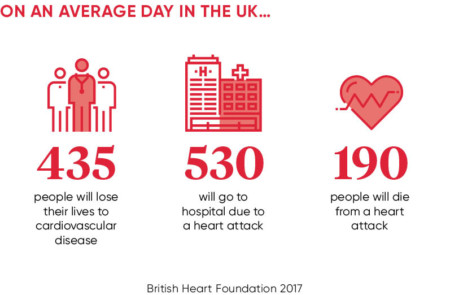

Yet still CVD affects around seven million people in the UK and is a significant cause of disability and death, affecting individuals, families and communities. CVD, essentially diseases of the heart and circulation, is the second highest cause of death after cancer, accounting for 27 per cent of all deaths each year, around 160,000. To put that into the starkest context, this amounts to one death every three minutes.

Lest we be tempted to think of this as a uniquely British problem, global figures for the incidence of CVD are also bleak. CVD is the number-one cause of death globally; more people die annually from it than from any other cause. According the World Health Organization, an estimated 17.7 million people died as a consequence of CVD in 2015, representing 31 per cent of all global deaths. Of these deaths, an estimated 7.4 million were due to coronary heart disease and 6.7 million were due to stroke.

The absolute tragedy is that around 80 per cent of CVD deaths in the UK are attributed to preventable factors, such as obesity, poor physical activity, heavy drinking, eating unhealthy foods and smoking. These are, essentially, lifestyle choices that men and women make from an early age. Thousands of lives might be saved every year through what appear to be relatively simple changes in lifestyles and habits.

Not only do we know what causes CVD, but we also know who is most at risk and even where they live. Broadly speaking, early deaths from CVD are most common in the north of England, central Scotland and South Wales, and lowest in the south of England. But deaths can be broken down much further than that, almost by postcode. We know, for example, that the premature (under-75) death rate for Glasgow (126 per 100,000) is more than three times higher than for Chiltern in Buckinghamshire (36 per 100,000).

With that level of information at our disposal, it would appear relatively straightforward to agree a targeted approach to CVD prevention, identifying those most at risk and providing the information they need to make choices that probably will add years to their life expectancy. Yet CVD remains a scourge of our society, ending lives prematurely and leaving many others with life-shortening conditions such as diabetes and vascular dementia.

CVD can also have a serious impact on quality of life and cause considerable disability. Stroke survivors may lose their speech and have impaired mobility, and those with peripheral arterial disease may lose a limb. The breathlessness and exhaustion of severe heart failure can preclude even minimal daily activities and all of these can prevent people returning to employment.

In addition to the high human cost, CVD is also a significant drain on NHS resources and on the UK economy. NHS England spends more than £7 billion a year treating patients with CVD, while the total cost to the economy, including aftercare and sickness benefits, is believed to be around £30 billion.

CVD is one of the conditions most strongly associated with health inequalities. The poorer you are, the greater the risk. Smoking, physical inactivity and obesity are greater in lower socio-economic groups, and the burden of morbidity and mortality is disproportionately shouldered by the most deprived.

Mortality rates for CVD vary markedly by levels of deprivation. People in the most deprived decile experienced under-75 mortality rates of 105 per 100,000 from CVD compared with a rate of 59 per 100,000 in the least deprived decile in 2012-14. In layman’s terms, this represents a difference in life expectancy of many years, depending on whether you are poor or better off.

In a sense, CVD is a disease of our times. Current political discourse centres on the widening gap between rich and poor. Even the European Union referendum seemed to turn, in simplest terms, on differences between the haves and the have-nots. If we are serious about addressing society’s inequalities, there is no better place to begin than with the prevention and treatment of CVD.

Further, at a time when a cash-strapped state is forced to make tough decisions over how it spends taxpayers’ money, CVD raises profound questions about where government responsibility ends and where personal responsibility begins. CVD risk is strongly influenced by what we eat and what we drink, by how much exercise we do and how much we weigh.

The challenge is to help younger people break the cycle

There is no question that it becomes more difficult to manage our lifestyle when we are anxious about family finances and there is no job security. The consequences of poverty are far reaching. But too many people live the lives their fathers and grandfathers lived. They smoke because family and friends have always smoked, and they drink alcohol regularly because their family and friends have always done so.

The challenge is to help younger people break the cycle. We must find engaging ways to make the public health agenda relevant to them and to find role models who can inspire them to challenge the way their parents lived. It is no easy task.