The big success story of pension savings in the UK is auto-enrolment. Insights from behavioural economics were used to create the scheme in 2012 to “nudge” more people into saving a percentage of their income in workplace pension schemes.

Employees can choose to opt out of the pension scheme, but given that many are not aware of the fact that they’re saving into a pension automatically, opt-out rates have been very low.

The scheme’s success is down to the power of inertia. But the flipside of inertia is that employees hardly engage with their pension savings. Indeed, only a third of workers realise workplace pension schemes are invested in the stock market, according to recent research from Hargreaves Lansdown.

Many don’t realise they can actively change what their pension is invested in. Does this level of apathy and lack of understanding pensions hinder or help pension providers?

Do pension providers win from customer apathy?

“Pension providers do not encourage their customers to decide to switch to other funds and there seems an in-built assumption that people are not interested and will not bother to make active decisions,” says former pensions minister Baroness Ros Altmann.

She notes that the more traditional final salary pensions did not typically permit members to choose their investments and the trustees are responsible for all such decisions, which again means pension savers never needed to engage with investment decisions.

“This lack of engagement can be beneficial to pension providers, because they do not face tough scrutiny from customers,” says Lady Altmann. “The complexity of products and lack of transparency have often allowed a proliferation of high hidden charges, which were not in the member’s interest.”

The pros and cons of default funds

Most workplace pension schemes will invest employees automatically into the scheme default fund, explains Victoria Rutland, chartered financial planner at EQ Investors. Typically, this means that during the early stages of a person’s pension savings, the fund heavily invests in equities and then proceeds to move into lower-risk assets such as bonds or cash, as people approach retirement.

However, as Rutland points out, for most of our working life, our pension is predominantly invested in equities, which means it can fluctuate significantly. “Many people would be shocked to see how much the value of their pension has fluctuated in the last six months in particular,” she says. You could therefore argue that people’s apathy towards their pension protects them from panicking about their savings when the stock market fluctuates.

Why do providers offer this type of default strategy? Rutland says: “Because it’s cost effective. Putting everyone into this type of strategy means that everyone can invest in the same way as others who are the same age as them. Each provider can simply make changes to one portfolio. The cost of providing advice to every single investor in each group scheme would be prohibitive.”

A more ethical way to invest your pension

But as more people endeavour to live sustainably, attention might turn to the actual contents of their pension pot. In Australia, Dr Bronwyn King, an oncologist, famously persuaded Australian pension funds to divest from tobacco.

“The majority of default funds, including lifestyle strategies, will be invested in ‘traditional’ investments such as shares in oil and gas companies, tobacco and armaments,” says Rutland. “Traditional investments don’t usually consider the carbon footprint of the underlying companies or the governance of the business and its supply chain.

“While a lot of opportunities to invest in ethical, ESG [environmental, social and governance] or positive impact portfolios are becoming more and more available on the wider market, workplace pensions are behind the curve.”

With increasing awareness, the tables could turn if people begin to take more control of their pension, changing funds en masse. In the UK, campaigns like Make My Money Matter by Comic Relief’s Richard Curtis, could contribute to bringing ESG investing to a mainstream audience by asking what is your pension invested in? But any form of pension activism has to be balanced with people’s need for financial literacy and advice.

Striking a balance between apathy and activism

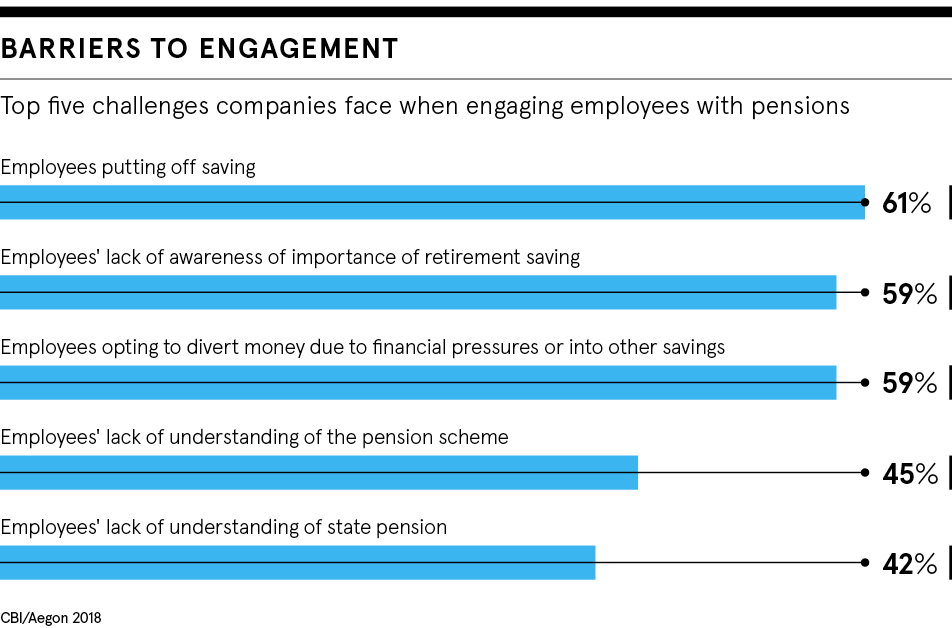

How can the industry find a happy balance between apathy and activist investing? Kate Smith, head of pensions at Aegon, says: “Nowadays, individuals have to shoulder much more responsibility for funding their retirement than ever before, so getting people properly engaged as early as possible in their working life is key.

“We want to see more savers engaged with their pensions, including reviewing their investment choices and monitoring investment performance. This is a good thing for providers and savers. Currently, fewer than one in five UK workers say they have used an investment-risk tool to find out how much risk they are comfortable with when investing in their pension.”

She notes that while many providers allow savers to carry out online fund switches, free of charge, few savers take advantage of this. The majority remain invested in the default fund, out of choice or apathy. “In reality, we think it’s highly unlikely that savers will en masse make numerous investment fund switches,” Smith adds. “And doing so will not necessarily lead to good member outcomes.”

For now, apathy and a lack of transparency are still endemic in pensions, despite years of attempts to improve engagement. As Lady Altmann concludes: “Improvements have been achieved, but only very slowly. I believe the industry should face up to this challenge and help its customers understand and engage with pensions.”

Driving engagement

Nest was set up by the government to ensure every UK employer could offer a workplace pension to their employees when auto-enrolment was introduced. It now has more than 9.3 million members and one in three of the working population is expected to have a Nest retirement pot by the late-2020s.

“Our view is that engagement is a necessary tool in helping our members achieve better outcomes in retirement,” says Eve Read, Nest’s director of business delivery. She argues that a combination of efforts is required. “We issue regular communications on topics that matter to members, which will be personalised to their own situation as much as possible,” Read says.

“For some individuals, the way to create engagement is to make it real for them, such as sharing how Nest is committed to tackling climate change, but for others it might be highlighting that they could build their pension pot faster by maximising tax savings or employer-matched contributions.” She says greater engagement could help pension schemes gain insights such as their members’ desired retirement age or retirement income.

“However, the biggest challenge of a very active model would be that members may then engage in highly complex decisions without fully understanding the profound impact these might have on their financial future. So, when we communicate with our members, we have to think really carefully about what we want them to think, feel and do, so we don’t inadvertently drive behaviours that might undermine their long-term goals,” Read concludes.

The big success story of pension savings in the UK is auto-enrolment. Insights from behavioural economics were used to create the scheme in 2012 to “nudge” more people into saving a percentage of their income in workplace pension schemes.

Employees can choose to opt out of the pension scheme, but given that many are not aware of the fact that they’re saving into a pension automatically, opt-out rates have been very low.