In August 2014, persons unknown opened a locked valve and released the oil lubricant from a steam turbine at Doel 4 nuclear plant just outside Antwerp, Belgium, causing it to overheat and break. Although the turbine was in a non-nuclear area of the site, it was a wake-up call for security.

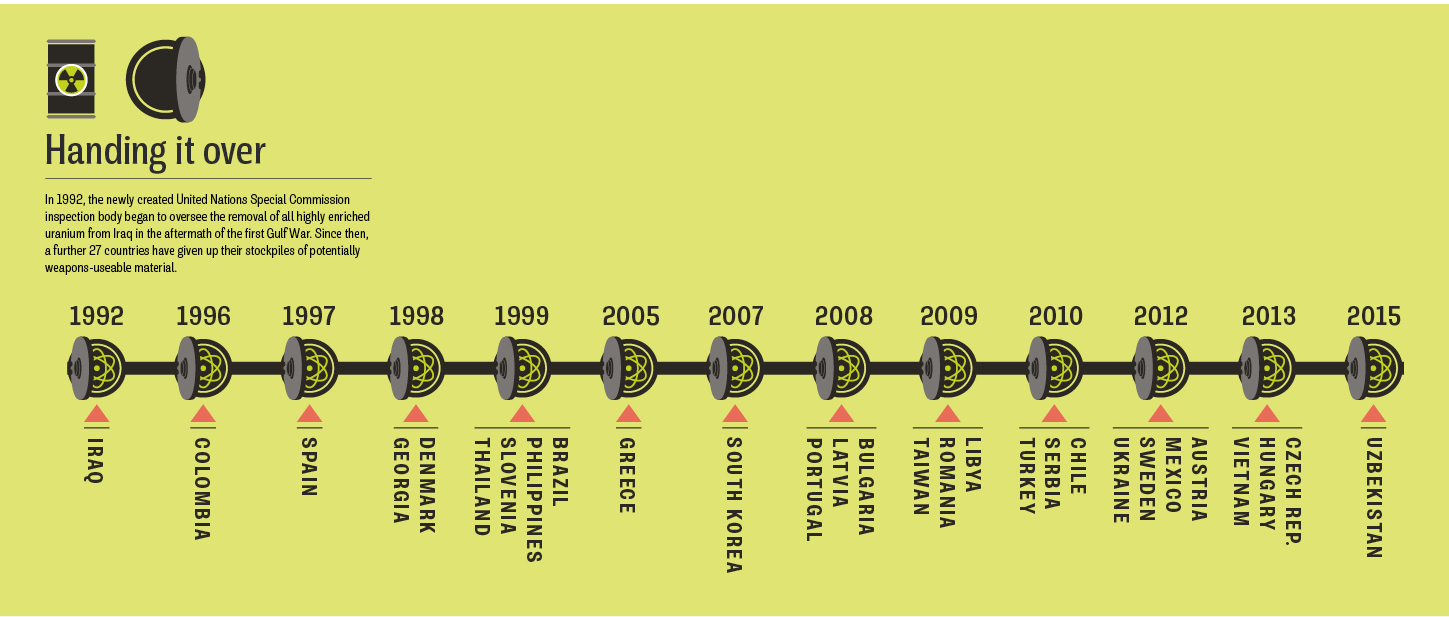

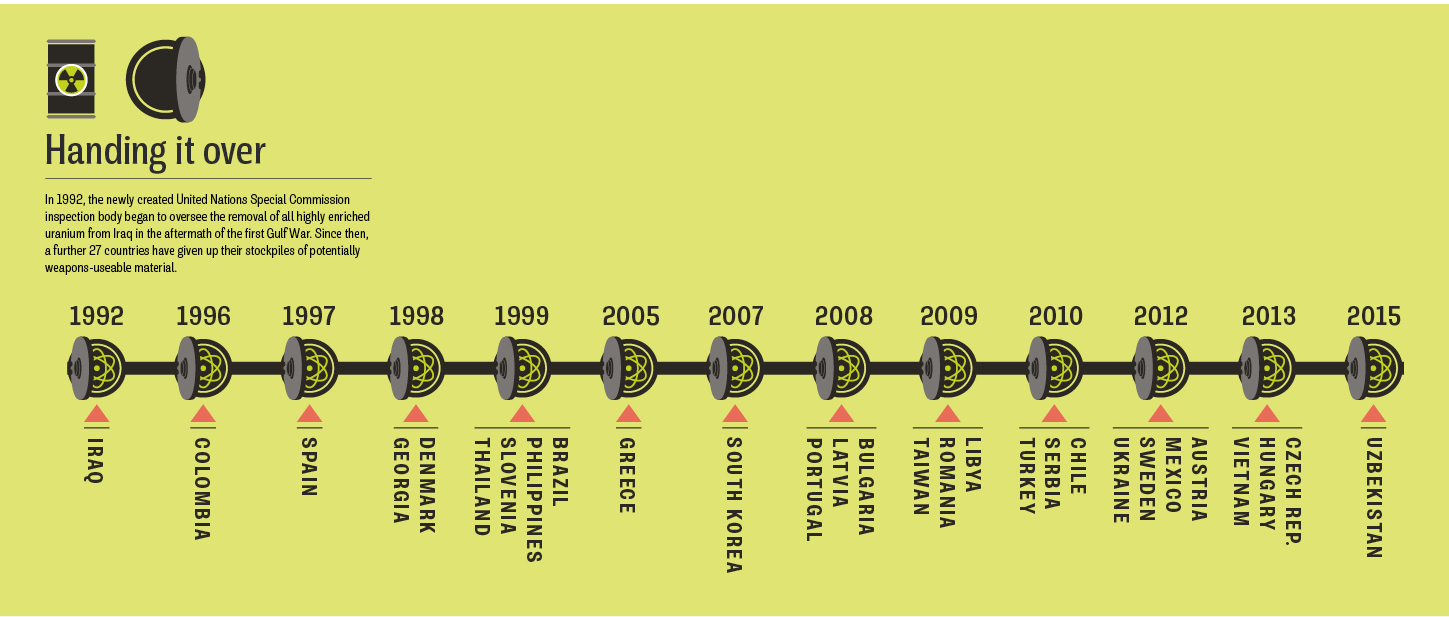

Click here for the full infographic

Looking into the sabotage, investigators were alarmed to find that two years earlier, a contractor at the plant with access to secure areas, had resigned to travel to Syria and join the so-called Islamic State. Just over a year later, as the hunt for the terror cell responsible for the November 2015 Paris attacks centred on Belgium, police raided a flat in Auvelais, a small, rural town in the south. Inside, they found surveillance footage of an employee of a facility that holds highly enriched uranium, the radioactive material that is the core component of nuclear weapons.

“After those events, Belgium has now decided, finally, to have armed guards at its nuclear facilities,” says Matthew Bunn, a professor at Harvard University’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs and a former nuclear safety specialist in the US government.

World leaders — with the exception of Russia, which has declined to participate — are meeting March 31 and April 1 in Washington for a summit on nuclear security, hoping to conclude new global agreements that will address the vulnerabilities that have allowed enriched uranium to leak out onto the black market.

Currently, there is no global treaty or regulation that sets a minimum standard for security of nuclear material. Although most potentially dangerous material is monitored by the International Atomic Energy Agency, “there are a few weird stocks here and there that get lost”, says Bunn, who was part of a US mission to remove Georgia’s highly enriched uranium in 1998. In December 2015, the IAEA announced it had removed another 1.83kg from the capital, Tbilisi, after another unregistered batch came to light.

Policymakers fear that frozen conflicts on the fringes of the former Soviet Union, in particular South Ossetia and Transnistria, could become hotspots for the smuggling of nuclear material. Endemic corruption in Russia, Pakistan and other nuclear states increases the risk that HEU could be sold on.

“The best opportunity we have in keeping it out of terrorist hands is keeping it from being stolen in the first place,” Bunn says. “Once it’s been stolen, all of the things we can do… are variations of looking for needles in haystacks.”

[embed_related]

What is HEU?

“Enriched” uranium is a vital component of civilian and military nuclear programmes. Uranium is a chemical element that has three naturally occurring atomic forms, or isotopes. Uranium-235 (235U), so-called because of its atomic weight, is fissile — meaning that it can be broken apart to create a nuclear chain reaction. However, it typically makes up less than 1 per cent of mined uranium.

Enriched uranium is uranium in which the amount of the 235U has been increased artificially. Highly enriched uranium, or HEU, is around 20 per cent composed of 235U. There are about 2,000 tonnes of the material in the world.

What could go wrong?

Iran — By the summer of 2009, Iran’s nuclear programme was progressing at a speed that was alarming its international opponents. Then, suddenly, the centrifuges used to enrich uranium at the Natanz nuclear facility began to systematically fail.

The culprit was later identified as a computer virus, Stuxnet, which had infected the plant’s software and damaged the centrifuges by increasing the pressure inside them. Widely believed to be a deliberate attack on the programme carried out by Israel and the USA, Stuxnet demonstrated how vulnerable real-world facilities are to virtual incursions.

According to the Nuclear Threat Initiative, out of the 45 states that operate nuclear facilities that could pose a serious threat in the event of sabotage, 20 lack even the basic requirements to protect their plants from cyber attacks.

Moldova — The former Soviet republic of Moldova is a centre of the black market in nuclear materials. Between 2010 and 2015, local police, aided by the FBI, have made four major seizures, totalling several kilograms of uranium.

USA — In 2012, Megan Rice, an 82-year-old nun, broke through four fences to gain access to the Y‑12 National Security Complex nuclear facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Rice and two fellow protestors spent more than two hours in the restricted area before they were caught by security.